OWL-3: A Picture Is Worth A Thousand Room Descriptions

by John Bilodeau

This is the third in a series of articles I call “The rest of the F#@king Owlbear” about making art for tabletop role playing games. This month I want to talk to TTRPG creators about drawing informative maps.

A picture is worth a thousand room descriptions

How often do you buy a module for your group and run it as is?

What can you tell about the rooms in a dungeon from the average module map? Its horizontal dimensions? Maybe the mapmaker drew doors in the doorways… if you’re in luck there is a trapdoor indicated, a statue, or maybe a stairway down. If you need more info, look to the accompanying pages and pages of text. Once you find the text describing that room, If you’re lucky, there will be some boxed text you can read aloud to your players.

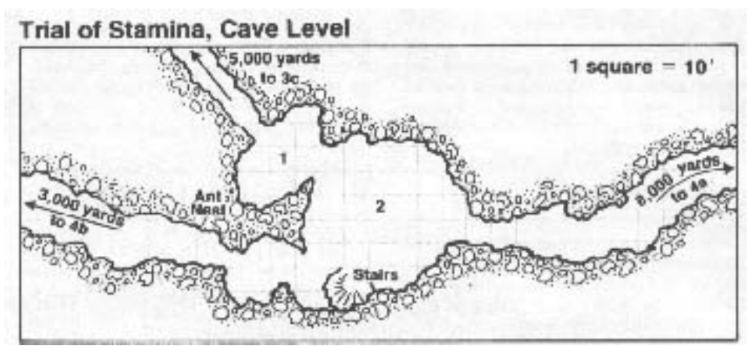

Here’s an example from an AD&D module (Blood & Laurels, Adventure Pack 1, 1987). I think it illustrates a missed doodling opportunity:

Let’s look at room 1… what can you tell about it from the map drawing? It has irregular stone walls and a sort of weird oblong shape more than 30 feet at its widest. The words “Ant Nest” are written in the solid stone of the cave.

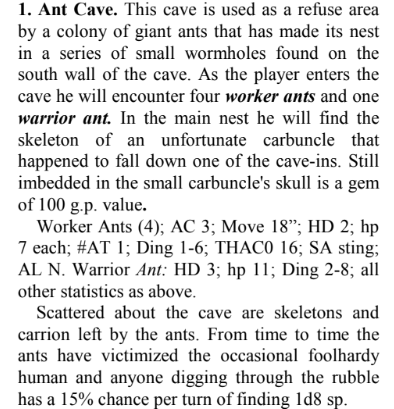

Here’s the text (in this case, luckily, it was on the same page as the map):

Now, I think almost all of this info could have been doodled on the map. One of the three paragraphs here are stats for giant ants which honestly could be handwaved by a good referee (the worker ants are pretty weak, the warrior is a little tougher) - if you draw a skull with a gem in it, the referee could decide how much it was worth.

To be honest, these stats kinda make it clear you are fighting these nerd ants, but I think the workers would leave the second you intruded.

With a good drawing you could convey what the room looks like, what’s in there and even a bit about the behaviour of the creatures you find there.

Here’s a quick example of a more illustrated map (or doodled map, actually). It’s a little bigger than the original empty map, but think of the space you could save without the paragraphs of descriptive text.

Give Stefan Poag a run for his money

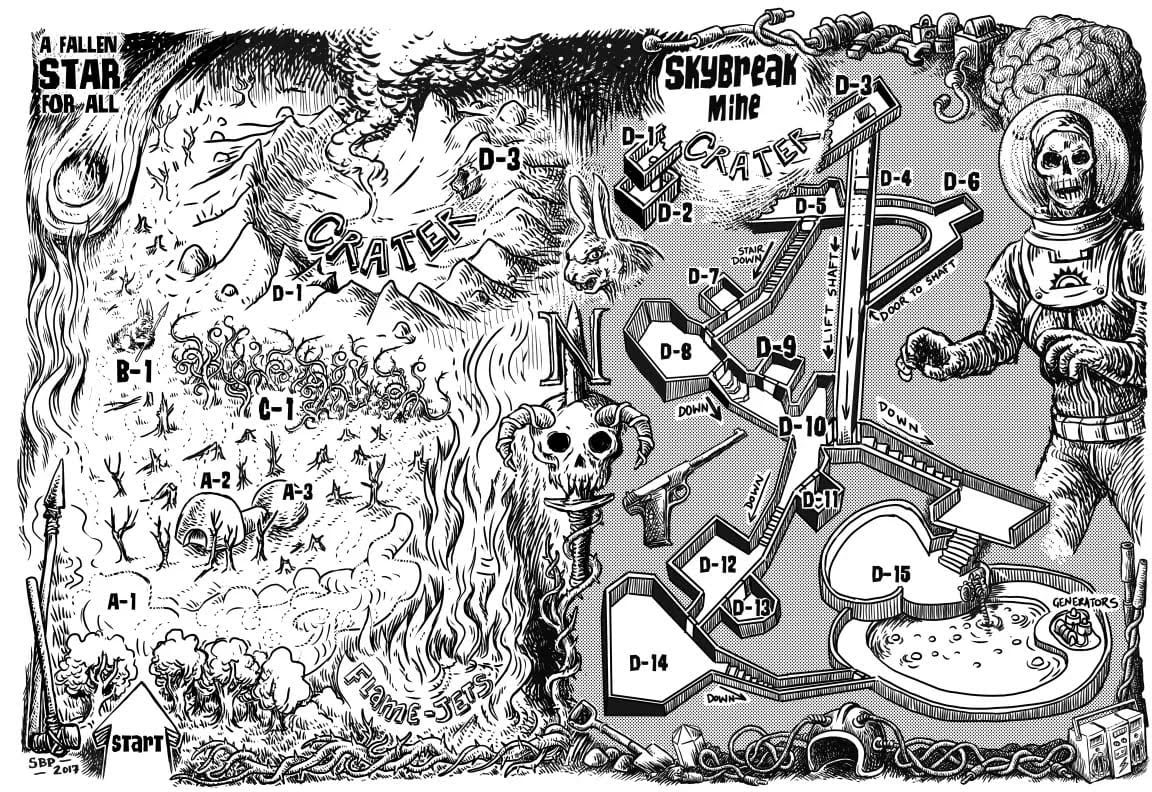

After the lock down portion of the pandemic I returned to playing in person TTRPGs by joining a DCC game at my local gaming store. This is where I ran into the mapping work of Stefan Poag. Since then my ideas about how much of the description of the adventure should be buried in text has changed. This is the map from one of my first adventures (I was a crowd of four 0 lvl peasants at the time):

I didn’t see this map until long after the adventure whose name I never knew, but I recognised it immediately. We fought those undead space diving suit guys… one of my characters got taken over by the facility by putting on the helmet drawn into the bottom border. I can also recognise the overland we moved through to get to the crater complex.

I love how Poag’s maps create a frame for the adventure. His maps provide information about the vibe and experiences the players will have in the course of their transit through the space.

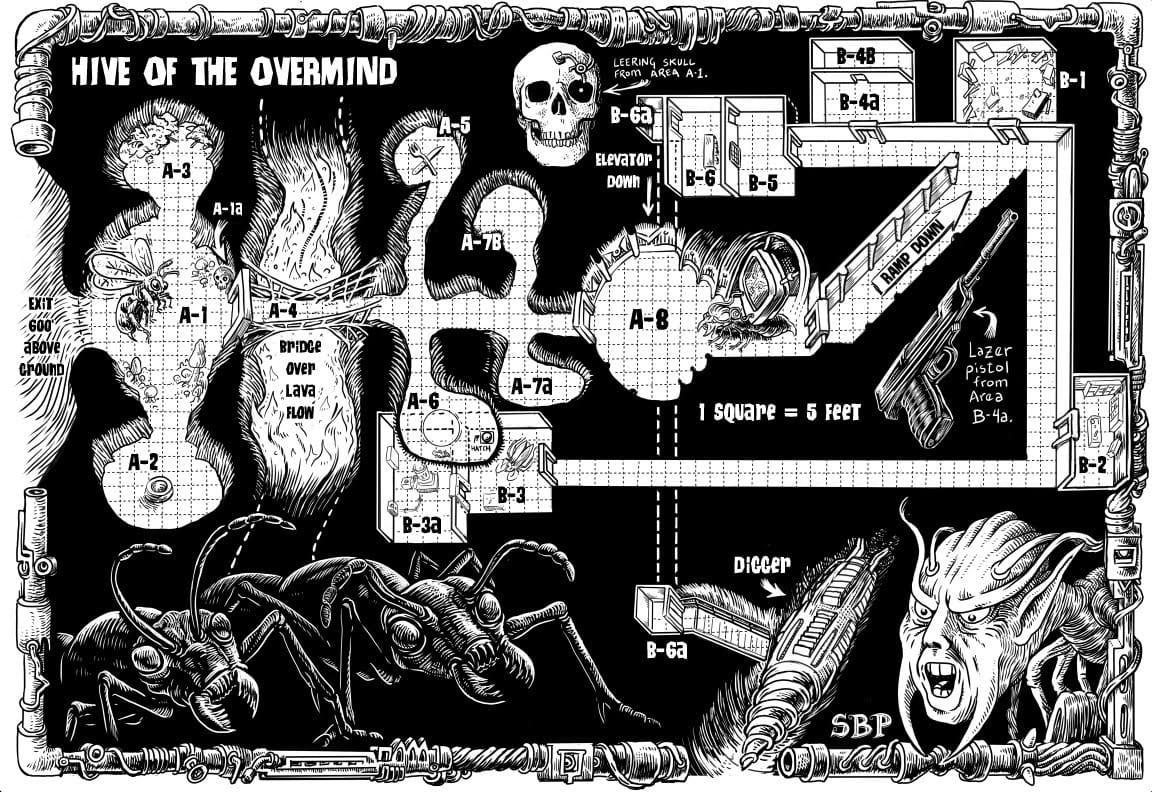

Compare Poag’s map for Hive of the Overmind to the AD&D map we were talking about before. Poag not only adds the relevant creatures and landmarks to the rooms themselves but he also fills the negative solace around the map will portraits of important elements to the adventure:

“Map is not Territory”

This phrase was coined by an earlier philosopher, but I came across the idea from Jonathan Z Smith when I was a religion undergrad. In the real world, it’s a reminder that our models and classifications of things aren’t the thing itself.

In the context of roleplaying games, the phrase takes on a slightly different meaning, because it speaks to the role the map in the module plays. It links the creator’s vision of the space, to the referee’s, and then to the players’ “recording” of the territory. The map is a bridge between multiple imaginations. The author of the map, the reader of the map, and the players in the adventure all contribute to the creation of the terrain that is “actually” traversed. The maps the players draw on their way through the terrain frequently include the type of marginalia Poag includes with his images, describing not just space, but plotline beats and the relative importance of particular figures.

I think this attempt to mirror a player drawn map is Poag’s way to help communicate the essential elements of the adventure in a language that is quickly processed and open to interpretation in terms of details. I think you could run an adventure successfully using just the map and some quick rationalization.

Level up to doodle maps

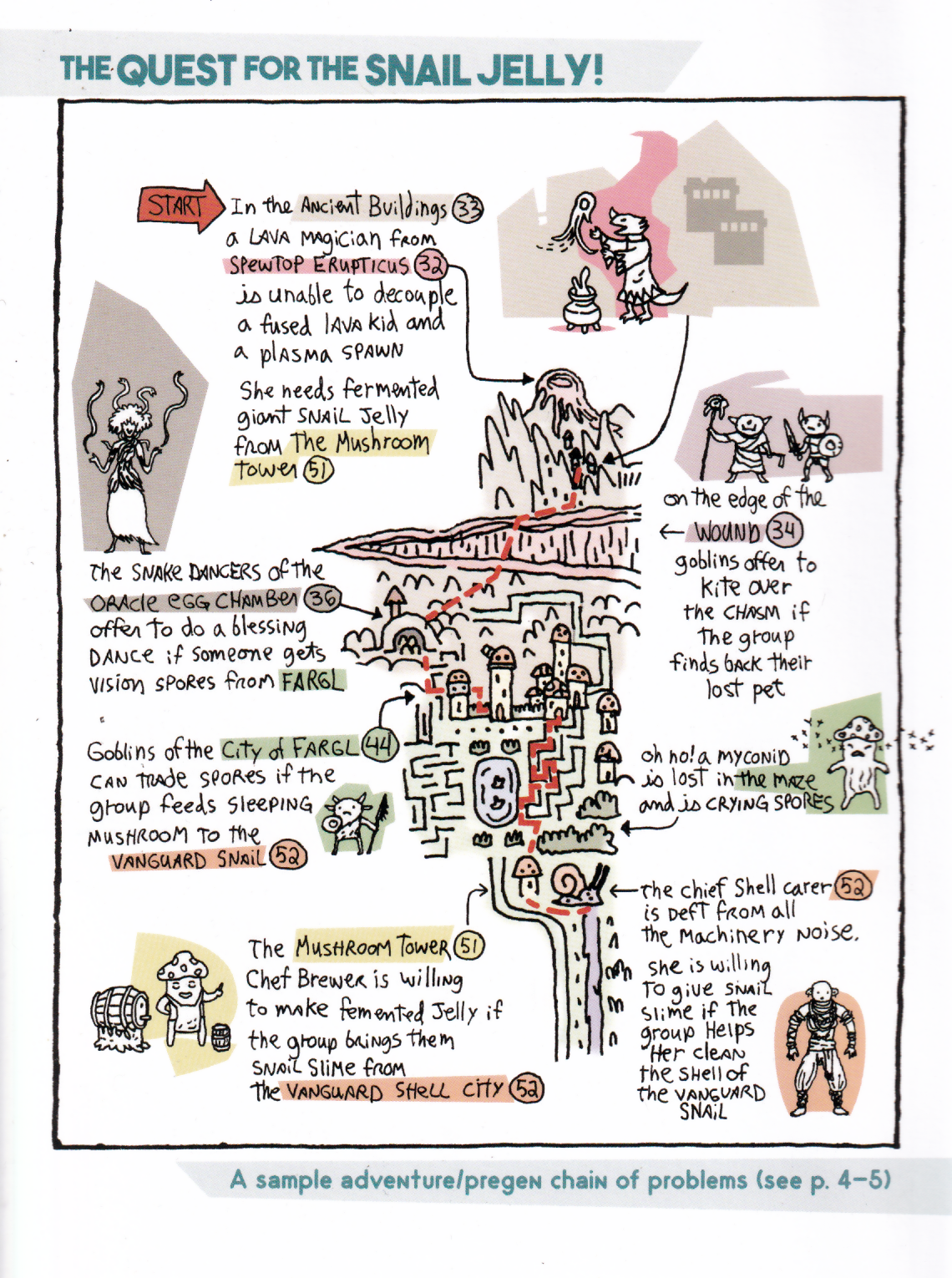

Think about everything you want the person reading your work to know, then draw it in the map. When it comes to doodle maps, the absolute best of the genre is the creator of the Doodleland game, Evlyn Moreau. Check out this beauty:

From: https://evlyn.itch.io/doodle-land

The circled numbers in the adventure outline are references to the Doodleland overland map.

So much of the vibe is communicated without words and the referees and players are free to move through the doddle space together. In a world of doodles, the player map would be so close to the module’s I bet they’d be close to interchangeable.

When you are creating your modules, remember that the map you provide is the link between the space you envision and the space the referee is presenting and the players are recording. A picture is worth a thousand words, so don’t bury your vision in text.

Collective Feedback

I ran this article past a few people in its preparation and got some more great suggestions about this style of mapping.

Rowan suggested people check out Michael of Undelved:

https://undelved.itch.io/beneath-the-spindle

And my friend Ingnan Wei recommended the youtube Odd Artworks:

https://www.youtube.com/@oddartworks

And Anna Blaskwell’s solo map drawing game, Delve:

https://blackwellwriter.itch.io/delve-a-solo-map-drawing-game